Why I Design and Print My Own Parts (Even When a File Already Exists)

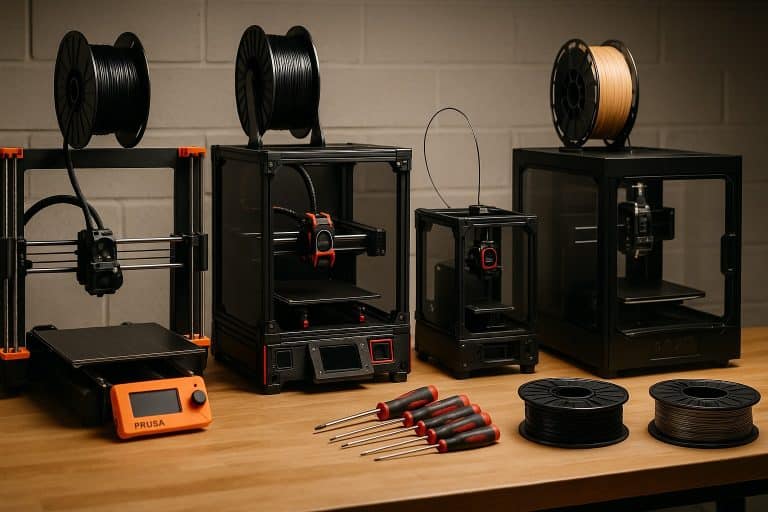

There’s this moment every maker knows. You find the perfect STL online — it fits your dimensions, looks clean, probably works great. And yet… you open your CAD program anyway. Not because you have to, but because something inside you wants to see if you can design your own parts and build it yourself.

For me, that’s the spark — that little voice that says, “Let’s figure this out.” Designing my own parts isn’t about saving time or showing off. It’s about learning, flexing creativity, and solving problems in a way that keeps me thinking. It’s about making things that fit my exact needs — and, just as importantly, understanding why they work.

That’s the core of my MYOG (Make Your Own Gear) philosophy. Whether I’m sewing a new pouch or designing a rack mount, creating something for myself brings a kind of satisfaction that downloading a file never could.

The Real Reasons I Design My Own Parts

Every time I start a new design, I’m signing up to learn something — even if it’s just refreshing a skill I haven’t used in a while. Sometimes I’m refactoring an old design to make it more efficient — looking at it with fresh eyes and finding a cleaner way to solve the same problem. And yes, I still love exercising my creativity while I do it. Designing forces me to slow down, think critically, and visualize how something fits together before I hit print.

And there’s something freeing about it — knowing that whatever I make will fit my setup perfectly. It’s not just another part that works; it’s a part that works for me. That’s the beauty of MYOG in a nutshell: the intersection of creativity and utility.

This all ties back to my MYOG philosophy — What MYOG Means to Me — where making for yourself is as much about curiosity as it is about capability.

Iteration Is the Hidden Teacher

One of my favorite examples of this mindset comes from my new 10-inch rack project. At first glance, it seemed straightforward — just a few plates, holes, and rack nuts. It can’t really be that hard right? I started with a test print just to hold the rack nut. It took me a few iterations to get the sizing right. I learned my original goal of pushing the nuts into place was never going to work. it also showed me my initial thoughts about the seemingly square nut being square was…..obtuse. I then had to get the sizing right for the rack nuts to spring into place and hold themselves accordingly. Finally, I felt ready to design my first u. I put all the measurements it, printed it out, and……man was I way off.

Back to my design. Looking at it and I realized my first orientation was impossible. A couple quick edits to rotate the spring arms 90 degrees and presto. Pretty close now. Just some fine tuning to get the holes to match within acceptable tolerances, then I can tackle the rest of the design.

I took a similar approach to building my own home lab rack mounts. If you’d like to see how that project evolved, check out my 10-Inch Rack Mount Build Story.

Each version taught me something new — about design constraints, print tolerances, even the feel of different materials. I’ve learned to view failed prints not as mistakes but as checkpoints. Each one gets me closer to a part that truly works. That’s the kind of learning you just can’t get from downloading a ready-made file.

Problem Solving and the “Martian” Mindset

One of my favorite lines from The Martian comes from Mark Watney: “You solve one problem. Then you solve the next one. And if you solve enough problems, you get to go home.” That’s exactly how I think about design. Every project starts as a big, complex problem — something I don’t fully understand yet. The trick is to break it into smaller, solvable parts.

Interestingly, this mindset actually traces back to NASA’s engineering culture. During the Apollo missions, engineers were trained to deconstruct huge challenges into manageable, testable pieces. It’s how they solved the near-impossible problems of spaceflight — and it’s the same mindset that shaped The Martian. That iterative, analytical approach is pure NASA DNA.

And that’s what designing my own parts feels like sometimes. It’s a mini engineering mission — test, analyze, improve, repeat. Whether I’m adjusting hole spacing or reworking a mounting angle, I’m channeling a bit of that NASA problem-solving mindset. It’s a form of creative engineering where failure is just another step toward success.

Creativity and Ownership

Designing your own parts gives you total creative control. You’re not constrained by someone else’s vision or priorities — you’re solving your problem. Maybe it’s a mount that fits your exact gear layout or a case that aligns with how you actually use your tools. The details matter because they’re personal.

There’s pride in that process, too. Even if my design isn’t the most elegant or efficient, it’s mine. I know every dimension, every tolerance, every tiny decision that went into it. It’s the same feeling I get when sewing a bag or building an antenna — a sense of ownership and satisfaction that comes from making something from scratch.

Applying the Lessons Beyond 3D Printing

The more I design, the more I notice how this mindset shows up everywhere else — especially in sewing. You don’t start by making a complicated backpack; you start by learning to sew straight seams or add a zipper. Each skill builds on the last, and before long, you’re tackling projects you never thought you could do.

Iteration, measuring, refining — it’s all the same process, just with different materials. In 3D printing, I use calipers and slicers; in sewing, it’s tape measures and fabric scissors. But the mentality stays the same: learn something small, master it, then move on to the next challenge.

That’s MYOG in its purest form — whether it’s nylon, plastic, or aluminum, you’re always learning by making.

Why I’ll Keep Making My Own

At the end of the day, designing from scratch is about curiosity and growth. It keeps me thinking, experimenting, and learning. Sure, there are faster ways to get a working part, but none of them are as rewarding.

Every design, every small iteration, teaches something new. And that’s what keeps me hooked. Because even if someone else has already made the perfect file, I haven’t made my version yet — and that’s reason enough to keep creating.